How Many Inner Nodes

Motivation

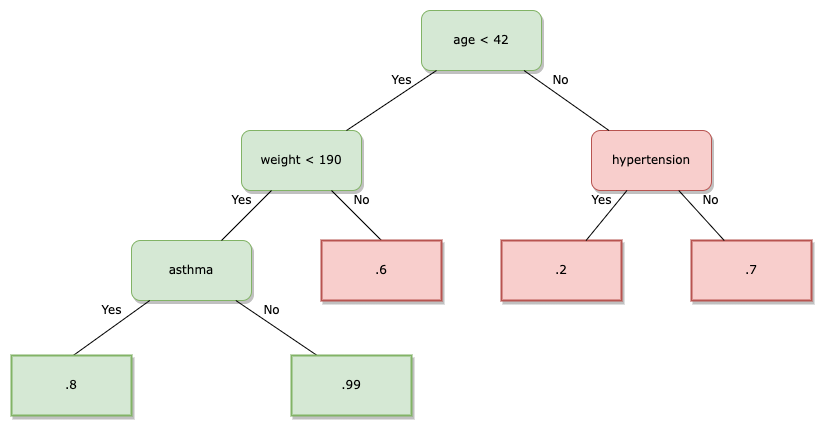

Assume you are working with a decision tree which as been constructed by a learning algorithm. Further assume that some of the leaves are relevant while others aren’t. For example, it could be that the outcome modeled in leaves corresponds to the probability of a successful surgery. In order to use this model for prediction/inference in production, one might imagine stripping all of its unnecessary parts. To be concrete, all of the leaves with a success probability which is no sufficiently high become irrelevant: the applicant might define a threshold, e.g. 80%, and not carry out a surgery below that probability. In this case, the applicant doesn’t care whether the prediction was 50% or 30% - just below 80%.

Yet, if certain leaves become irrelevant, it might also be that certain inner nodes become irrelevant. It could be that entire paths in the tree - conjunctions of logical predicates - become unnecessary to represent in our production application.

Let us illustrate this based on the example from above.

Since all patients with age > 42 have a success probability of below 80%, we don’t need the inner node splitting on hypertension. Yet, the node splitting on weight is necessary even though one of its direct descendant leaves is not necessary.

This bears the question: If some leaves are not necessary, how many of all available inner nodes will are necessary?

Problem formulation

Let’s first assume that we are dealing with complete binary trees where the root has depth 0. Moreover, we will assume that every leaf is relevant with a probability of $q$, i.i.d.

Formally speaking, we would like to ask two questions:

- In expectation, what is the fraction of inner nodes that need to be kept?

- How does this fraction behave as a function of $q$ and the depth $d$?

How many of the inner nodes need to be kept?

Let us first recall that $\Pr[\text{leaf is kept}] = q$.

Then, we can ask the question of how likely it is that an arbitrary inner node of depth $i$ will be kept. We observe that it will be kept if at least one if its descendant leaves will be kept. Conversely, it will not be kept if all of its descendant leaves will not be kept.

$$\begin{aligned} \Pr[\text{given inner node necessary}] &= 1 - \Pr[\text{all leaf descendants are not kept}] \\ &= 1 - \prod \Pr [\text{given leaf is not kept}] \\ &= 1 - \prod (1 - q) \\ &= 1 - (1 - q)^{2^{d-i}} \end{aligned}$$

where we have used the independence of the leaves and the fact that the subtree of an inner node at depth $i$ of a tree of depth $d$ comprises $2^{d-i}$ leaves.

Now, we might want to come back to our first question: how many inner nodes are kept in expectation?

$$\begin{aligned} \mathbb{E}[\text{\# inner nodes necessary}] &= \mathbb{E}[\sum \mathbb{I}[\text{given inner node necessary}]] \\ &= \sum \mathbb{E}[\mathbb{I}[\text{given inner node necessary}]] \\ &= \sum \Pr[\text{given inner node necessary}] \\ &= \sum_{i=0}^{d-1} \sum_{\eta = 1}^{2^i} \Pr[\text{given inner node } \eta \text{ of depth } i \text{ necessary}] \\ &= \sum_{i=0}^{d-1} 2^i (1 - (1 - q)^{2^{d-i}}) \end{aligned}$$

where we used the linearity of expectation.

As a consequence, since a complete tree of depth $d$ has $\sum_{i=0}^{d-1} 2^i = 2^d -1$ many inner nodes, the ratio of inner nodes necessary corresponds to

$$ \frac{\sum_{i=0}^{d-1} 2^i (1 - (1 - q)^{2^{d-i}})}{2^d -1} = \frac{2^d -1 - \sum_{i=0}^{d-1} 2^i(1 - q)^{2^{d-i}}}{2^d -1} = 1 - \frac{\sum_{i=0}^{d-1} 2^i(1 - q)^{2^{d-i}}}{2^d -1}$$

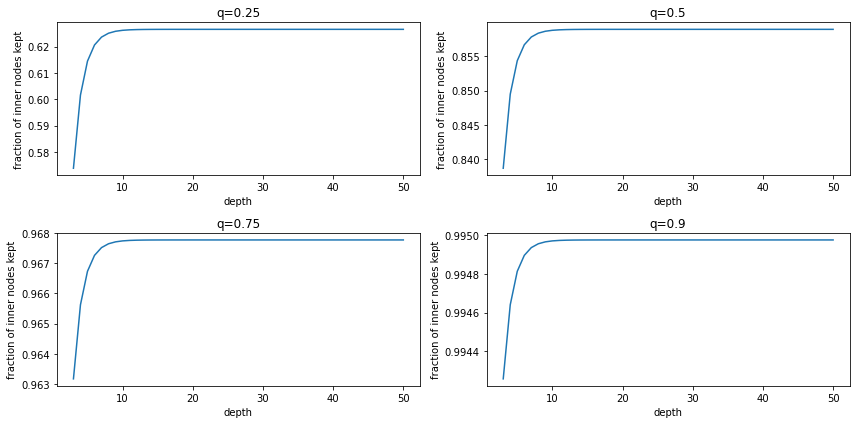

With that, we have in principle - albeit without a neat, closed form - answered our first question. If we plot this fraction for increasing $d$ and a number of different $q$, we observe the following:

These plots make it seem as though for a given $q$, the fraction of kept inner nodes was converging to an asymptote with growing depth. This brings us to our second question: How does the fraction behave for varying $q$ and depth $d$?

The plot from above gives hope that the fraction converges to a constant for any $q$, with growing $d$. Let’s now try to back this up formally. In light of this, let’s recall the Cauchy ratio test. In short, it can tell us that a series $a_n$ converges if $\lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} |a_{n+1} / a_n| < 1$. Recalling our fraction from before we therefore pose that

$$a_d := \frac{\sum_{i=0}^{d-1} 2^i(1 - q)^{2^{d-i}}}{2^d -1}$$

If we instantiate this series for a couple of indices, we might be able guess a recursive form:

$$\begin{aligned} a_1 &= (1-q)^2 \\ a_2 &= \frac{1}{3} ((1-q)^4 + 2 (1-q)^2) \\ a_3 &= \frac{1}{7} ((1-q)^8 + 2 (1-q)^4 + 4(1-q)^2) \end{aligned}$$

We can see (or prove by induction) that

$$a_d = \frac{1}{2^d - 1} (2 (2^{d-1} - 1) a_{d-1} + (1-q)^{2^d})$$

We shall now use this recursive definition for the Cauchy ratio test:

$$\begin{aligned} \lim_{d \rightarrow \infty} |\frac{a_{d+1}}{a_d}| &= \lim_{d \rightarrow \infty} \frac{a_{d+1}}{a_d} \\ &= \lim_{d \rightarrow \infty} \frac{2 (2^{d} - 1) a_{d} + (1-q)^{2^{d+1}}}{(2^{d+1} - 1)a_d}\\ &= \lim_{d \rightarrow \infty} \frac{2^{d+1} - 2}{2^{d+1} - 1} + \frac{(1-q)^{2^d}}{(2^{d+1} - 1)a_d} \\ &= 1 + \lim_{d \rightarrow \infty} \frac{(1-q)^{2^d}}{(2^{d+1} - 1) \frac{\sum_{i=1}^{d-1} 2^i (1-q)^{2^{d-i}}}{2^d - 1}} \\ &= 1 + \lim_{d \rightarrow \infty} \frac{(1-q)^{2^d}}{\frac{2^{d+1} - 1}{2^d - 1} \sum_{i=1}^{d-1} 2^i (1-q)^{2^{d-i}}} \\ \lim_{d \rightarrow \infty} \frac{(1-q)^{2^d}}{\frac{2^{d+1} - 1}{2^d - 1} \sum_{i=1}^{d-1} 2^i (1-q)^{2^{d-i}}} &\leq \lim_{d \rightarrow \infty} \frac{(1-q)^{2^d}}{\frac{2^{d+1} - 1}{2^d - 1} 2^{d-1} (1-q)^2} \rightarrow 0 \end{aligned}$$

Where we have used that a sum of positive elements is greater or equal any element for the inequality and the fact that the last numerator goes to 0 with $d \rightarrow \infty$ while both factors of the numerator got to $\infty$ as $d \rightarrow \infty$.

Sadly, this tells us that the limit of the ratio is 1 and therefore we cannot conclude just yet that the series converges.

Yet, we can argue differently that $a_d$ converges, and thereby $1 - a_d$, too. Since every term of the series is a product of positive sub-terms, every term of the series is positive. Moreover, we observe that the series is upper-bounded:

$$\begin{aligned} a_d &= \frac{\sum_{i=0}^{d-1} 2^i(1 - q)^{2^{d-i}}}{2^d -1} \\ &\leq \frac{\sum_{i=0}^{d-1} 2^i}{2^d -1} \\ &=\frac{2^d - 1 }{2^d -1} = 1 \end{aligned}$$

As a consequence, we know that $a_d$ converges to a constant below 1. Yet, we don’t know what this value is.

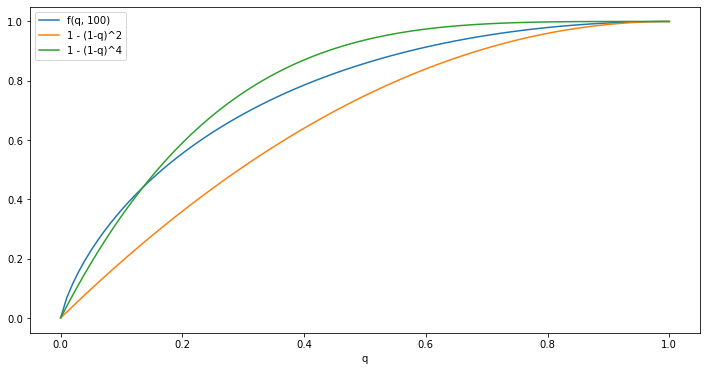

Conversely, we can attempt to obtain a feeling for how $1 - a_d$ - i.e. the fraction of necessary inner nodes - behaves for different $q$, with constant, ’large’ depth $d$:

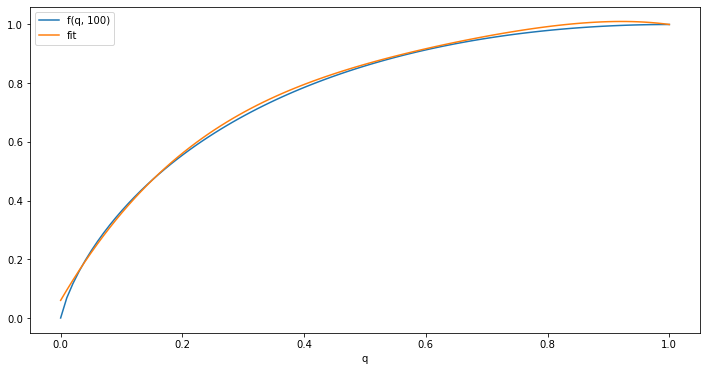

Furthermore, we can fit a polynomial up to degree 4 with least squares:

It seems fair to say that above fit can serve as a rough approximation. Hence:

$$\lim_{d \rightarrow \infty} 1 - a_d \approx 1 - 2.3 (1-q)^4 + 3.2 (1-q)^3 - 2.1 (1-q)^2 + 0.3(1-q)$$

What we can say for sure is that the fraction of necessary inner nodes grows faster than $q$. Put differently, for every leaf we’d like to keep, we need overproportionally many inner nodes.