Who With Whom, What With What

The following is an illustration of a graph optimization problem. I chose to instantiate it with a decision making process revolving around a social setting. Yet I hope its general applicability comes across.

Setup

Let’s say we have the opportunity to invite people to an event. The pool of candidates is comprised of five people: Tony, Paulie, Silvio, Furio and Vito. What we care about is for the attendants to have a good time - which we assume to be purely determined by who else is attending. If two people like each other and are both present, their experience improves. Put differently, we can think of ‘value’ that the presence of a pair of people has1. Moreover, we assume that this pairwise value is independent of who else is there. For example, the presence of Tony is as valuable for Paulie when Silvio is presents as when Silvio is absent.

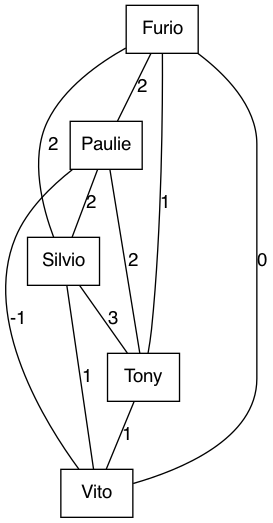

The following graph illustrates this situation; vertices representing people and edge weights representing pairwise value.

Given that we cannot have all people over, but rather just \(n\), we would like to maximize the overall value created by the gathering, in true utalitarian fashion.

Solution

As was previously mentioned, we can model every candidate as a vertex in a graph \(G = (V, E)\). Since we assume to know what the value of each co-occurrence is, we have a complete graph. In other words, every vertex is connected to every other vertex. Moreover we have edge weights \(w\) from an arbitrary numerical range, possibly negative.

Our challenge lies in finding a sub-graph/clique of cardinality \(n \leq |V|\) such that the sum of edge weights is maximal. We can formalize this to resemble to an integer linear program (ILP):

$$ \max_{S} \sum_{e_{i, j} \in E} \mathbb{I}[i \in S] \mathbb{I}[j \in S] w(e_{i, j}) \\ s.t.\ S \subset V, |S| = n $$

Note that this is not an integer linear program quite yet. As of now, the product of indicator variables as well as the set notation are beyond scope. Therefore we will reprhase these slightly.

For that matter, we introduce binary variables \(x_{v_i}\) representing \(\mathbb{I}[v_i \in S]\) as well as binary variables \( x_{e_{i, j}} \) representing \( \mathbb{I}[e_{i, j} \in E]\). Thanks to the nature of our problem formulation – we always assume a subgraph to be complete – the set of selected edges logically follows from the set of selected vertices. Yet, since explicit logical conjunctions, i.e. \(x_{e_{i, j}} = x_{v_i} \wedge x_{v_j}\), are usually not permitted in integer linear programming, we have to find a way to create an implicit logical conjunction. We do so by imposing lower and upper bounds which ensure that intended behaviour 2:

$$\begin{aligned} & \max \sum_{i, j \in \mathcal{T}} x_{e_{i, j}} w_{i, j} \\ & s.t. \sum_{i \in \mathcal{I}} x_{v_i} = n \\ & \forall x_{e_{i, j}}: x_{e_{i, j}} \leq x_{v_{i}} \\ & \forall x_{e_{i, j}}: x_{e_{i, j}} \leq x_{v_{j}} \\ & \forall x_{e_{i, j}}: x_{e_{i, j}} \geq x_{v_{i}} + x_{v_{j}} - 1 \end{aligned}$$

where \( \mathcal{I}\) is a set of indices over all vertices/people and \(\mathcal{T}\) is a subset of \( \mathcal{I}^2\) such that

- no unordered pair of indices occurs twice and

- no index co-occurrs with itself

Translating this into Python code using PuLP, this could look as follows - given initialized friend_names and weight, as well as a SymmetricDict3:

import pulp

ilp = pulp.LpProblem("friends", pulp.LpMaximize)

vertex_variable = {}

for name in friend_names:

vertex_variable[name] = pulp.LpVariable(name=name, cat=pulp.const.LpBinary)

edge_variable = SymmetricDict()

for (i, j) in itertools.combinations(friend_names, 2):

edge_variable[(i, j)] = pulp.LpVariable(name=f"{i}-{j}", cat=pulp.const.LpBinary)

# Adding constraint ensuring edge is selected exectly when both of its vertices are selected.

ilp += edge_variable[(i, j)] <= vertex_variable[i]

ilp += edge_variable[(i, j)] <= vertex_variable[j]

ilp += edge_variable[(i, j)] >= vertex_variable[i] + vertex_variable[j] - 1

# Adding constraint ensuring exactly n vertices are selected.

ilp += sum(vertex_variable[i] for i in friend_names) == n

# Adding an objective function.

ilp += sum(

edge_variable[(i, j)] * weight[(i, j)]

for i, j in itertools.combinations(friend_names, 2)

)

ilp.solve()

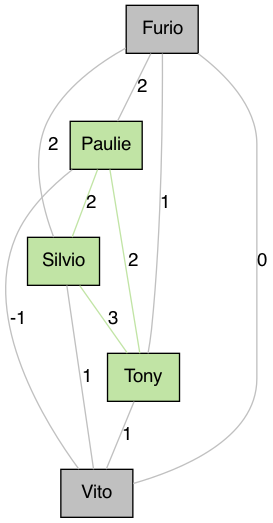

Running this for the example above with \(n=3\) leads to the following result:

Since solving an integer linear program is generally assumed to be NP-hard, we don’t have reason to believe that this approach works for large input sizes. More precisely, PuLP uses CBC as a default solver. I’m not sure which algorithm it uses under the hood for integer linear programs. Yet, Frank et al present an approach with runtime in \(c_v^{2.5 c_v} \mathcal{O}(poly(c_c, log(d)))\) where \(c_v\) is the number of variables, \(c_c\) the number of constraints and \(d\) the maximal value among constant coefficients. In our case we have

- \(c_v = |V| + {|V| \choose 2}\)

- \(c_c = 3 {|V| \choose 2} + 1\)

- \(d = n\)

This should yield an asymptotic complexity of \(\mathcal{O}(|V|^{|V|} \cdot poly(|V|^2, log(n)) \). :(

Non-solutions

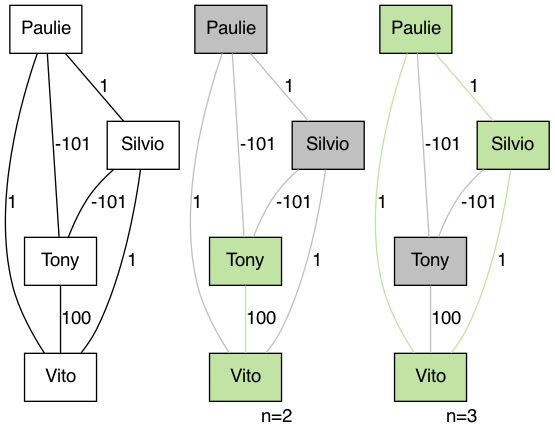

It is easy to show that the problem cannot be solved greedily. Consider the following graph:

We notice that the lavish edge weight between Tony and Silvio is a dealmaker for Tony to be part of the selection for \(n=2\), while Tony’s other terrible edge weights prevent him from being part of the selection for \(n=3\).

Based on a similar intuition I’m not particularly hopeful to solve this with dynamic programming.

I was wondering whether this problem could be reframed as a max flow min cut problem, which would allow for polynomial runtime complexity. So far I haven’t found a way to do so. That said, I also haven’t shown this problem to be in a particular complexity equivalence class. So who knows. Shimizu et al claim the slightly different maximum edge-weighted clique problem to be NP-hard. Yet, what is particular about our problem is that we know the size of the subgraph: \(n\). Hence, if we know \(n\) to be in in \(\mathcal{O}(1)\) with respect to the number of vertices \(|V|\), the brute force approach of runtime complexity \(\mathcal{O}({|V| \choose n} \cdot {n \choose 2})\) suddenly doesn’t look so bad any more.

The code accompanying this exercise can be found here.

For example, this pairwise value of Tony and Silvio being present could potentially express the mean of the value Tony creates for Silvio and the value Silvio creates for Tony. ↩︎

We observe that if \(\min(x_{v_i}, x_{v_j}) = 0\) then \(x_{v_i} + x_{v_j} -1 < 0\). Given the binary nature of the variables, this forces \(x_{e_{i, j}}\) to equal 0. If, on the other hand, \(\min(x_{v_i}, x_{v_j}) = 1\), we know that the lower and upper bounds align: \(x_{v_i} = x_{v_j} = x_{v_i} + x_{v_j} -1 = 1\). As a consequence it holds that \(x_{e_{i, j}} = 1\). ↩︎

Since we are operating on an undirected graph, the edge \(e_{i, j}\) is indistinguishable from the edge \(e_{j, i}\). The responsibility of accounting for this symmetry can either

- be delegated to the user of a data structure, e.g. by duplicating values (data redundancy :() or by defining an unambigious access pattern or

- be taken care of by the datastructure itself.

Here, I opted for the latter by writing a simple wrapper around the Python dictionary.

class SymmetricDict(dict): @classmethod def sort_tuple(cls, key): return tuple(sorted(key)) def __getitem__(self, key): key = self.__class__.sort_tuple(key) return super().__getitem__(key) def __setitem__(self, key, value): key = self.__class__.sort_tuple(key) return super().__setitem__(key, value)Fortunately, it seems to do what it’s supposed to do:

↩︎d = SymmetricDict() d[("Bob", "Anne")] = 5 d[("Anne", "Bob")] >>> 5 d[("Bob", "Anne")] >>> 5