Sudoku #1: Depth-First Search

Abstract

Solving a Sudoku board can be done in many ways. Let’s explore a depth-first search approach in this post.

Idea

Depth-first search or DFS implies (at least) two things:

- a graph, or rather, a tree

- a search

This bares the question: What’s the tree and what are we searching for?

The tree

A tree must consist of nodes and edges. We define the nodes to represent a ‘state’ of the game. A state of the game is meant to be a snapshot of the Sudoku board, i.e. a mapping from cells, e.g. 2nd row, 6th column, to values, e.g. 7 or ’empty’. Every edge in the tree represents an ‘action’, i.e. the addition or removal of a cell value.

Hence, given a state of the board, represented by a node, which nodes are its children?

In order to answer to that question, we must take the Sudoku rules into consideration:

- Pre-written digits cannot be overridden

- Only integers from 1 to 9 can be used.

- None of these integers may occur twice in the same row, column or square (only considering the 9 non-overlapping 3x3 squares)

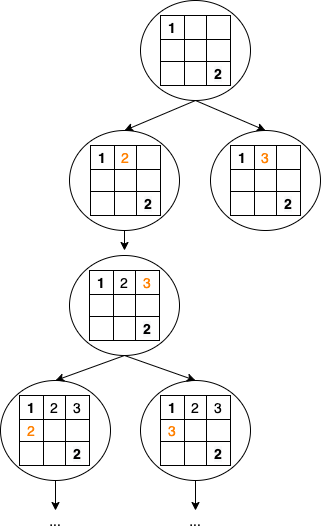

With that in mind, starting from a given node S, i.e. a state of the board, S’s children could consist of derived states which have one S’s empty cells filled with a digit that conforms to aforementioned rules.

The immediate application of these rules can be thought of as a trivial form of ‘pruning’, getting rid of all states that are already clearly not promising early on in the tree.

Moreover, we will enforce an arbitrary structure on the ‘parent-child’ relationship: instead of allowing any empty cells to be filled in the next action, we will only allow the ’next’ empty cell to be filled. W.l.o.g. we define ’next’ according to a left-to-right, top-to-bottom scan.

For illustrational purposes, let’s look into an example of a 3x3, instead of a 9x9 board:

Note that we hit a dead-end quite quickly.

The search

Now having an idea about what the semantics of our underlying tree look like, what are we looking for in this tree?

Given that every node of the tree represents not only an arbitrary state of the board but rather a state of the board consistent with Sudoku rules, we may now focus on Sudoku’s actual goal: completing the board. This is equivalent to saying that no cell is left empty.

Hence, in this tree, we look for a node whose state of the board comes without empty cells.

Moreover, we know that every suitable Sudoku puzzle comes with a unique solution, hence we must not care for distinguishing between several nodes statisfying this constraint.

As a side note, this problem can clearly also be tackled with breadth-first search. The latter’s usual appeal of finding the shortest path is not relevant in this particular application since all chains of actions arriving at the solution are of equal length: the number of empty cells.

Implementation

All things Sudoku start off with a board. While some other data structures might be handier for this task in some regards, I just went with a nested list for the sake of sticking with vanilla python. Note that 0 is employed as an indicator for empty cells.

board = [

[7, 8, 0, 4, 0, 0, 1, 2, 0],

[6, 0, 0, 0, 7, 5, 0, 0, 9],

[0, 0, 0, 6, 0, 1, 0, 7, 8],

[0, 0, 7, 0, 4, 0, 2, 6, 0],

[0, 0, 1, 0, 5, 0, 9, 3, 0],

[9, 0, 4, 0, 6, 0, 0, 0, 5],

[0, 7, 0, 3, 0, 0, 0, 1, 2],

[1, 2, 0, 0, 0, 7, 4, 0, 0],

[0, 4, 9, 2, 0, 6, 0, 0, 7],

]

All three non-obvious ‘rules’ of Sudoku rely on checking whether no integer between 1 and 9 occurs twice. In a way, these are the ‘same’ rule for a varying kind of ‘collection’: rows, columns, squares. Hence, we can write a function which takes such a collection and checks for uniqueness of said values:

def is_valid_collection(collection):

non_zeros = list(filter(lambda digit: digit != 0, collection))

n_non_zero_uniques = len(set(non_zeros))

return len(non_zeros) == n_non_zero_uniques

Yet, we don’t only want to check whether a row, a column or a square is ‘valid’ in a Sudoku sense. Rather we’d like to know whether all rows, all columns and all squares, i.e. the whole board is ‘valid’ in a Sudoku sense. For that we apply aforementioned is_valid_collection function on all rows, columns and squares. In light of that, we transform the board into lists of such ‘collections’, which comes for free in the case of rows, but needs minor transformations for columns, get_columns and squares get_squares.

def get_columns(board):

dimensions = range(len(board))

columns = [[] for _ in dimensions]

for row_index in dimensions:

for column_index in dimensions:

columns[column_index].append(board[row_index][column_index])

return columns

def get_squares(board):

dimensions = range(len(board))

squares = [[] for _ in dimensions]

for row_index in dimensions:

for column_index in dimensions:

square_index = row_index // 3 * 3 + column_index // 3

squares[square_index].append(board[row_index][column_index])

return squares

def is_valid_board(board):

has_valid_rows = all(map(is_valid_collection, board))

if not has_valid_rows:

return False

columns = get_columns(board)

has_valid_columns = all(map(is_valid_collection, columns))

if not has_valid_columns:

return False

squares = get_squares(board)

has_valid_squares = all(map(is_valid_collection, squares))

if not has_valid_squares:

return False

return True

So now we’re able to tell whether a given board satisfies the Sudoku conditions - sweet!

As previously mentioned, our transitions from state to state rely on trying out different candidates for the next empty cell. Remember the we defined ’next’ with regards to a left-to-right, top-to-bottom scan:

def get_next_empty_cell_indices(board):

for row_index in range(len(board)):

for column_index in range(len(board)):

if board[row_index][column_index] == 0:

return (row_index, column_index)

return None

Onto the real meat: the search! DFS can easily be implemented by explicit function recursion or by the use of a while loop and a stack. I opted for the former since I thought it was easier to read.

Our recursive function assumes to be given a valid starting board and should check for validity of new candidates before handing the board over to the new function call. Hence we don’t need to check validity at the beginning of a function call.

Therefore the next step is to identify what the indices of the next empty cell are:

def solve(board):

next_empty_indice = get_next_empty_cell_indices(board)

Just as CS 101 told us, every recursion ought to have a base case or success condition or whatever you want to call it. As we’ve argued before, we are searching for a state of the board in which no more cell is empty. get_next_empty_cell_indices returns None if no next index pair is found. Hence retrieving None is a proxy for having achieved our goal.

def solve(board):

next_empty_indices = get_next_empty_cell_indices(board)

if next_empty is None:

print("Solved!")

return board

Yet, most of the time, we are not done yet. In that case, we need to check all candidate values for validity. I figure there is a three-fold case distinction:

- No candidate is valid: we simply undo changes to the empty cell under investigation. This is basically pruning the tree; we know that this state will never lead to success and we would rather move up in the tree again, exploring other branches.

- At least one candidate is valid but none of its children lead to success. Do the same as above.

- At least one candidate is valid and one of its children leads to success. We simply propagate the state of that leaf up to the root and stop all action.

VALUES = range(1, 10)

def solve(board):

next_empty_indices = get_next_empty_cell_indices(board)

if next_empty_indeces is None:

print("Solved!")

return board

row_index, column_index = next_empty_indices

for candidate in VALUES:

board[row_index][column_index] = candidate

if not is_valid_board(board):

continue

solved_board = solve(board)

if solved_board is not None:

return solved_board

board[row_index][column_index] = 0

Disclaimers

Please note that this is brute in terms of the algorithm and naive in terms of the implementation. It’s solely meant to be a somewhat easy-to-follow and somewhat neat application of an algorithm many people have come across onto a problem most people have probably come across.

Code at https://github.com/kklein/sudoku.